Principal Component Analysis

Principal Component Analysis

In this post, I will be discussing Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and how it can be used in data sets to understand variation with many different variables. Many real-world data sets are often in high dimensions. In other words, they contain so many variables that it is difficult to distinguish a trend.

PCA is a type of dimensional reduction method that can assist us by identifying which variables contribute to the variation within the data. It is similar to fitting a best fit line onto a 2D graph, but in this case there may be more than three-dimensions of data. It is formulated in the language of linear algebra and is an often used technique in data science and bioinformatics.

library(ggplot2)

library(cowplot) # required to arrange multiple plots in a grid

library(dplyr)

##

## Attaching package: 'dplyr'

## The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':

##

## filter, lag

## The following objects are masked from 'package:base':

##

## intersect, setdiff, setequal, union

Exploring the data

We will be using the often cited iris data set. As you can see, there

are more than five dimensions of data.

head(iris)

## Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species

## 1 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2 setosa

## 2 4.9 3.0 1.4 0.2 setosa

## 3 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2 setosa

## 4 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2 setosa

## 5 5.0 3.6 1.4 0.2 setosa

## 6 5.4 3.9 1.7 0.4 setosa

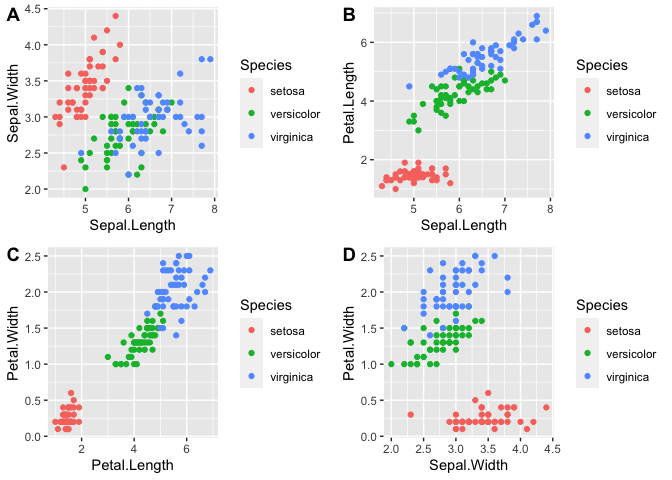

Let us try to observe some patterns with different combinations of variables.

p1 <- ggplot(iris, aes(x=Sepal.Length, y=Sepal.Width, color=Species)) + geom_point()

p2 <- ggplot(iris, aes(x=Sepal.Length, y=Petal.Length, color=Species)) + geom_point()

p3 <- ggplot(iris, aes(x=Petal.Length, y=Petal.Width, color=Species)) + geom_point()

p4 <- ggplot(iris, aes(x=Sepal.Width, y=Petal.Width, color=Species)) + geom_point()

plot_grid(p1, p2, p3, p4, labels = "AUTO")

As you can see from the graphs, petal length, petal width, and perhaps sepal length contribute the most to the differences between the three species.

Using PCA

Let’s try using PCA as a better method for detecting such patterns.

First, we will only include numerical data. We will pass our data set

(excluding the Species column) into the function prcomp. center and

scale will be set to true to scale the data to 0 mean and unit

variance.

iris.pca <- prcomp(iris[,1:4], center = TRUE, scale. = TRUE)

summary(iris.pca)

## Importance of components:

## PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4

## Standard deviation 1.7084 0.9560 0.38309 0.14393

## Proportion of Variance 0.7296 0.2285 0.03669 0.00518

## Cumulative Proportion 0.7296 0.9581 0.99482 1.00000

The main results are that Principal Components 1 and 2 explains the majority of the variance within the data set. These values are derived from the eigenvectors and eigenvalues from the covariance matrix.

To better understand, you will need a basic understanding of eigenvectors and eigenvalues. To simply put, an eigenvector is a vector whose direction remains unchanged after a linear transformation. In that regard, an eigenvector provides direction or orientation of the data, like 90 or 45 degrees. The change after a linear transformation is described as the eigenvalue. In other words, the variance or spread of the data is explained by the eigenvalue. In addition, an n-th dimensional matrix will have the same n eigenvectors/eigenvalues. Therefore, each principal component is an eigenvector and PC1 has the highest eigenvalue (highest variance).

We can observe the results of the linear transformation with

iris.pca$x.

head(iris.pca$x)

## PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4

## [1,] -2.257141 -0.4784238 0.12727962 0.024087508

## [2,] -2.074013 0.6718827 0.23382552 0.102662845

## [3,] -2.356335 0.3407664 -0.04405390 0.028282305

## [4,] -2.291707 0.5953999 -0.09098530 -0.065735340

## [5,] -2.381863 -0.6446757 -0.01568565 -0.035802870

## [6,] -2.068701 -1.4842053 -0.02687825 0.006586116

Let’s add back in the species data.

pca_data <- data.frame(iris.pca$x, Species=iris$Species)

head(pca_data)

## PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4 Species

## 1 -2.257141 -0.4784238 0.12727962 0.024087508 setosa

## 2 -2.074013 0.6718827 0.23382552 0.102662845 setosa

## 3 -2.356335 0.3407664 -0.04405390 0.028282305 setosa

## 4 -2.291707 0.5953999 -0.09098530 -0.065735340 setosa

## 5 -2.381863 -0.6446757 -0.01568565 -0.035802870 setosa

## 6 -2.068701 -1.4842053 -0.02687825 0.006586116 setosa

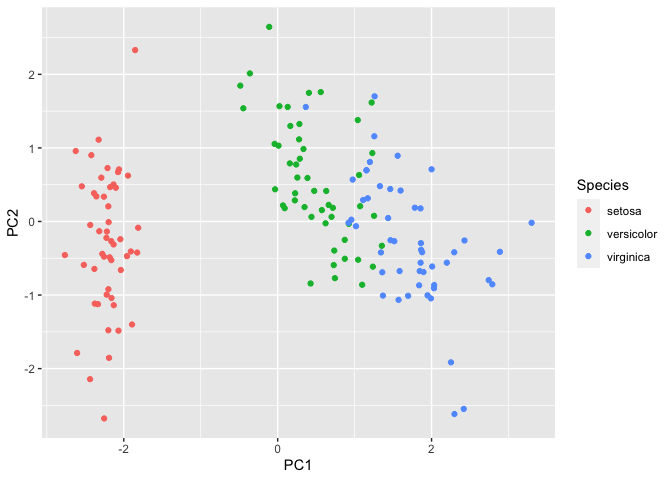

Next, we will plot the first two principal components as these would explain the highest variation within the data.

ggplot(pca_data, aes(x=PC1, y=PC2, color=Species)) + geom_point()

We can observe that setosa separates further from versicolor and

virginica. To understand which variables contribute to this variation in

the data, we will call iris.pca$rotation.

iris.pca$rotation

## PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4

## Sepal.Length 0.5210659 -0.37741762 0.7195664 0.2612863

## Sepal.Width -0.2693474 -0.92329566 -0.2443818 -0.1235096

## Petal.Length 0.5804131 -0.02449161 -0.1421264 -0.8014492

## Petal.Width 0.5648565 -0.06694199 -0.6342727 0.5235971

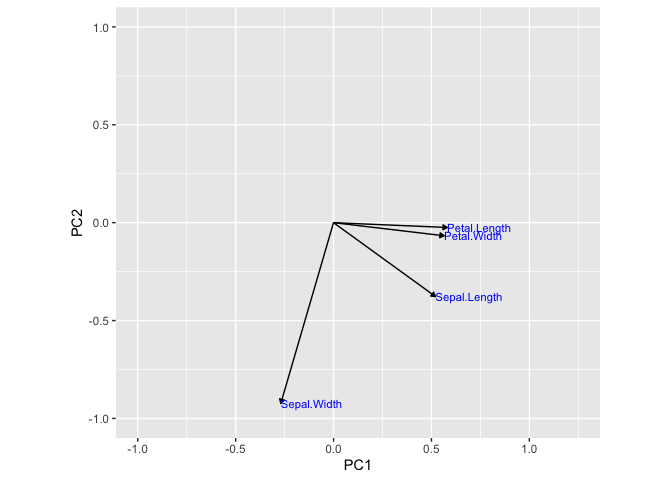

Here we can see that Sepal.Length, Petal.Length, and Petal.Width

contributes quite a bit to PC1 compared to Sepal.Width. However,

Sepal.Width contributes greatly to PC2.

Therefore, based on the above graph, we can infer that variance in the

x-axis is due to Sepal.Length, Petal.Length, and Petal.Width and

variance in the y-axis is due to Sepal.Width. Running the following

code will show this concept as vectors.

# capture the rotation matrix in a data frame

rotation_data <- data.frame(iris.pca$rotation, variable=row.names(iris.pca$rotation))

# define a pleasing arrow style

arrow_style <- arrow(length = unit(0.05, "inches"),

type = "closed")

# now plot, using geom_segment() for arrows and geom_text for labels

ggplot(rotation_data) +

geom_segment(aes(xend=PC1, yend=PC2), x=0, y=0, arrow=arrow_style) +

geom_text(aes(x=PC1, y=PC2, label=variable), hjust=0, size=3, color='blue') +

xlim(-1.,1.25) +

ylim(-1.,1.) +

coord_fixed() # fix aspect ratio to 1:1

As you can see, before performing a PCA, we used four graphs to observe the conclusion that petal length, petal width, and sepal length contributed the most to the variance in species. With PCA, we could easily observe this with the PCA plot of PC1 vs PC2. In addition, we used a simple dataset to illustrate this. Many real-world data sets consists of much higher dimensions.