Gradient Descents

Gradient Descents

In this post, we are going to discuss Gradient Descents; what it is and how to use it. Gradient Descent is used in many machine learning algorithms to find the local minimum in differentiable functions where there is a linear relationship. It goes hand in hand with optimization problems. In this tutorial, we will focus on linear regressions. A linear regression is used to model the relationship between one or more variables. In our case, we have an input $x$ and an output $y$, but we do not know the slope $m$ or the intercept $b$.

\[y = mx + b\]To build our model, we need to tune two parameters, namely $m$ and $b$ . To do so, we need to use the mean squared error (MSE) as our loss function. This function measures the average squared difference between the estimated values and the actual value. We expect this to be 0 if our predicted values equal our actual value.

\[MSE =\frac{1}{N}\Sigma_{i=1}^{n}(Y_{i}-\hat Y_{i})^{2}\]Therefore, we will need optimize the MSE for a linear regression using the gradient descent. A gradient is defined as follows:

\[\nabla J(\theta) = [\frac{\partial J}{\partial\theta_{1}},\frac{\partial J}{\partial\theta_{2}},...,\frac{\partial J}{\partial\theta_{p}}]\]The gradient descent is defined in the following equation. The algorithm will iterate over and over using the gradient descent to find new values of $m$ and $b$ . This will continue until MSE converges to zero, letting us know that our predicted values equal to our actual values.

\[\theta_{n + 1} =\theta_{n} -\eta\nabla J(\theta_{n})\]Let’s first solve for $\nabla J(\theta_{n})$ by plugging in the MSE equation and finding the partial derivatives with respect to $m$ and $b$.

\[MSE =\frac{1}{N}\Sigma_{i=1}^{n}(y_{i}-(mx_{i}+b))^{2}\] \[f(m,b) =\frac{1}{N}\Sigma_{i=1}^{n}(y_{i}-(mx_{i}+b))^{2}\] \[\frac{\partial f(m,b)}{\partial m} =\frac{1}{N}\Sigma_{i=1}^{n}-2(y_{i}-(mx_{i}+b))\frac{\partial f}{\partial m}(mx_{i}+b))\] \[\frac{\partial f(m,b)}{\partial m} =\frac{1}{N}\Sigma_{i=1}^{n}-2x_{i}(y_{i}-(mx_{i}+b))\] \[\frac{\partial f(m,b)}{\partial b} =\frac{1}{N}\Sigma_{i=1}^{n}-2(y_{i}-(mx_{i}+b))\frac{\partial f}{\partial b}(mx_{i}+b))\] \[\frac{\partial f(m,b)}{\partial b} =\frac{1}{N}\Sigma_{i=1}^{n}-2(y_{i}-(mx_{i}+b))\]Now we have our two final equations. We can begin implementing them.

\[\hat m = m -\eta(\frac{1}{N}\Sigma_{i=1}^{n}-2x_{i}(y_{i}-(mx_{i}+b)))\] \[\hat b = b -\eta(\frac{1}{N}\Sigma_{i=1}^{n}-2(y_{i}-(mx_{i}+b)))\]We will input two vectors $x$ and $y$ and solve for $m$ and $b$. In addition, we set a learning rate, $\eta$ of 0.001. This controls the magnitude of the gradient. If it is too large, we will miss the minima, but if it is too small, the number of iterations will increase. For this function, we will iterate 10,000 times and break the loop if $MSE\le\epsilon$, $\epsilon = 0.001$.

gradient_descent <- function(x,y, epsilon = 0.001, lr = 0.001, steps = 10000){

epsilon = 0.0001

m = runif(1) #Initialize a random number

b = runif(1) #Initialize a random number

N = length(x)

log = c()

mseloss = c()

for (step in 1:steps){

f = y - (m*x + b) #Subtracting the estimated value from the actual value

mseloss = c(mseloss, sum(f ** 2) / N)

dm <- -2 / N * sum(x %*% f)

db <- -2 / N * sum(f)

m = m - lr * dm

b = b - lr * db

log = rbind(log, c(m,b))

if (sum(f ** 2) / N <= epsilon){ #stop the algorithm once we have converged to zero

break

}

}

list = list('m' = m, 'b' = b, 'steps' = step, 'log' = log, 'mseloss' = mseloss)

return(list).

We can initialize a simple example by setting x = c(1,2,3,4,5) and

y = 2 * x. We expect m = 2 and b = 0.

x = c(1,2,3,4,5)

y = 2 * x

ptm <- proc.time()

res <- gradient_descent(x,y)

proc.time() - ptm

## user system elapsed

## 0.723 0.454 1.185

res$m

## [1] 1.992251

res$b

## [1] 0.02797554

cat('The predicted values are:', head(res$m * x + res$b))

## The predicted values are: 2.020227 4.012478 6.004729 7.99698 9.989232

cat('\nThe actual values are:', head(y))

##

## The actual values are: 2 4 6 8 10

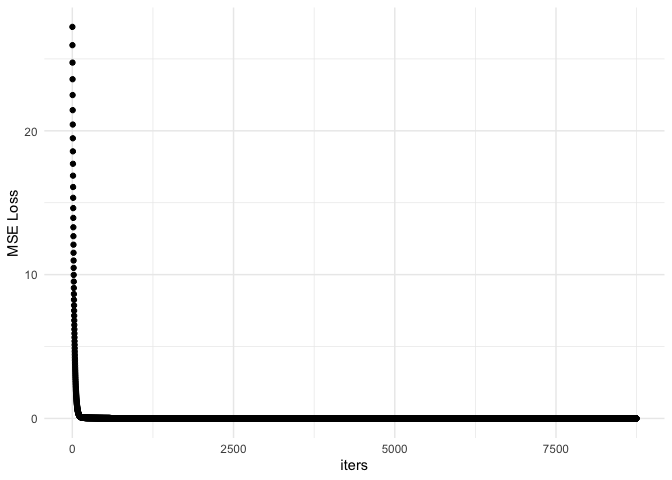

We can observe convergence by plotting the MSE against the number of iterations.

library(ggplot2)

df <- data.frame('iters' = 1:res$steps, 'mseloss' = res$mseloss)

ggplot(df, aes(x = iters, y = mseloss)) + geom_point() + theme_minimal() + ylab('MSE Loss')

It appears to converge early but continues on to meet our requirement of $MSE\le\epsilon$ . Let’s repeat this with a larger data set. We would expect this to take longer.

x = runif(10000)

y = 2 * x

ptm <- proc.time()

res <- gradient_descent(x,y)

proc.time() - ptm

## user system elapsed

## 2.542 1.425 4.022

res$m

## [1] 1.577939

res$b

## [1] 0.2254082

cat('The predicted values are:', head(res$m * x + res$b))

## The predicted values are: 0.8785615 0.6359393 1.200908 0.628451 1.231726 0.5944415

cat('\nThe actual values are:', head(y))

##

## The actual values are: 0.8278561 0.5203383 1.236423 0.5108471 1.275484 0.4677408

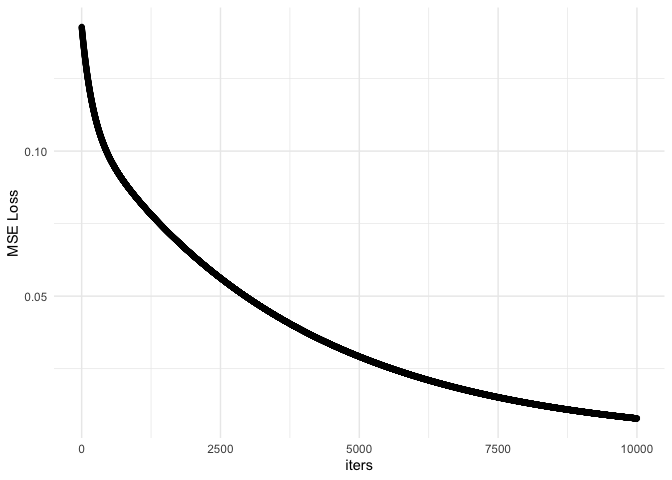

df <- data.frame('iters' = 1:res$steps, 'mseloss' = res$mseloss)

ggplot(df, aes(x = iters, y = mseloss)) + geom_point() + theme_minimal() + ylab('MSE Loss')

As you can see, the predicted values don’t match the actual values. In addition, the MSE loss does not converge. This suggests we may need more iterations. Let’s try with 50,000 iterations.

ptm <- proc.time()

res <- gradient_descent(x,y, steps = 50000)

proc.time() - ptm

## user system elapsed

## 9.538 5.721 15.327

res$m

## [1] 1.965497

res$b

## [1] 0.01842688

cat('The predicted values are:', head(res$m * x + res$b))

## The predicted values are: 0.8320013 0.5297885 1.23352 0.5204611 1.271906 0.4780985

cat('\nThe actual values are:', head(y))

##

## The actual values are: 0.8278561 0.5203383 1.236423 0.5108471 1.275484 0.4677408

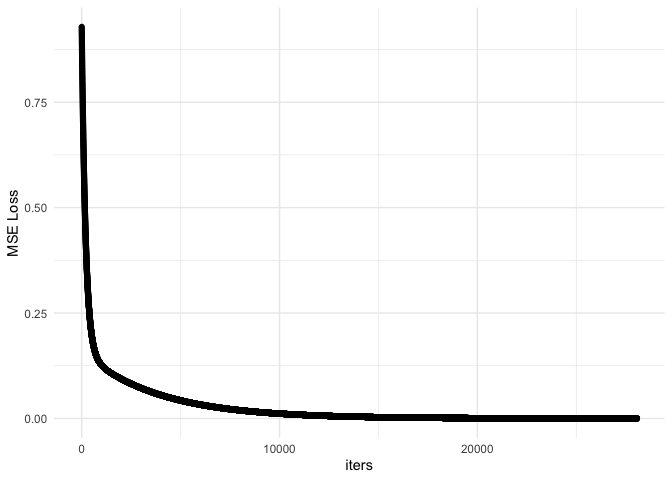

df <- data.frame('iters' = 1:res$steps, 'mseloss' = res$mseloss)

ggplot(df, aes(x = iters, y = mseloss)) + geom_point() + theme_minimal() + ylab('MSE Loss')

Comparing to Stochastic Gradient Descent

Now it looks like we have converged and reached an optimal value. However, the time it took was much longer. To wrap up, we were able to determine a suitable $m$ and $b$ to satisfy our optimization problem. However, this algorithm can be slow if we are working with large matrices. In that case, we can use Stochastic Gradient Descent and use only a subset of the matrix with one sample at a time for the optimization.

Let’s see what this would look like.

s_gradient_descent <- function(x,y, epsilon = 0.001, lr = 0.001, steps = 10000, batch_size = 1){

epsilon = 0.0001

m = runif(1) #Initialize a random number

b = runif(1) #Initialize a random number

log = c()

mseloss = c()

for (step in 1:steps){

index <- sample.int(length(y), batch_size)

N = length(index)

Xs <- x[index]

Ys <- y[index]

f = Ys - (m*Xs + b) #Subtracting the estimated value from the actual value

mseloss = c(mseloss, sum(f ** 2) / N)

dm <- -2 / N * sum(Xs %*% f)

db <- -2 / N * sum(f)

m = m - lr * dm

b = b - lr * db

log = rbind(log, c(m,b))

if (sum(f ** 2) / N <= epsilon){ #stop the algorithm once we have converged to zero

break

}

}

list = list('m' = m, 'b' = b, 'steps' = step, 'log' = log, 'mseloss' = mseloss)

return(list).

With the above function, we will only be using a subset of our data for optimization. In this case, I will set it to 100. Feel free to play around with the parameters.

ptm <- proc.time()

sgd_res <- s_gradient_descent(x,y, steps = 50000, batch = 100)

proc.time() - ptm

## user system elapsed

## 4.532 2.952 7.543

sgd_res$m

## [1] 1.961864

sgd_res$b

## [1] 0.02037149

cat('The predicted values are:', head(sgd_res$m * x + sgd_res$b))

## The predicted values are: 0.8324419 0.5307878 1.233218 0.5214777 1.271534 0.4791934

cat('\nThe actual values are:', head(y))

##

## The actual values are: 0.8278561 0.5203383 1.236423 0.5108471 1.275484 0.4677408

As you can see, we nearly cut out run time in half by just using stochastic gradient descent.